WHO Recognizes Hepatitis D Virus as a Cause of Liver Cancer

WHO Recognizes Hepatitis D Virus as a Cause of Liver Cancer

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) have officially classified the Hepatitis D virus (HDV) as a Group 1 carcinogen, a category reserved for substances and agents with proven evidence of causing cancer in humans. This classification firmly places HDV alongside Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) as recognized causes of liver cancer.

This announcement has significant implications for global public health, especially in regions where HBV and HDV remain prevalent. By acknowledging the direct cancer-causing potential of HDV, global health authorities hope to accelerate prevention strategies, testing, and treatment efforts to reduce liver cancer cases worldwide.

Understanding Hepatitis D (HDV)

Hepatitis D is a relatively uncommon yet extremely severe liver infection. Unlike other hepatitis viruses, HDV is unique because it cannot multiply on its own, it depends entirely on the presence of the Hepatitis B virus to replicate. This makes it what scientists call a “satellite” virus.

There are two primary ways HDV infection can occur:

- Co-infection – when a person is infected with HBV and HDV at the same time.

- Superinfection – when HDV infects someone who already has a chronic HBV infection.

Globally, HDV affects an estimated 12 million people, which is about 5% of all chronic HBV carriers. Despite being less common than HBV or HCV, HDV tends to cause more rapid and severe liver damage, increasing the risk of cirrhosis and cancer.

Who Issued the Classification?

The classification comes jointly from:

- WHO (World Health Organization) – the leading international public health body under the United Nations.

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) – WHO’s specialized cancer research agency.

By placing HDV in Group 1, they are stating with certainty that the virus causes cancer in humans. This group also includes well-known cancer-causing agents such as tobacco smoke, asbestos, ultraviolet radiation, and the viruses HBV and HCV.

Geographic and Risk Profile

HDV is not evenly distributed across the world. It tends to be more common in specific regions, including parts of Asia, Africa, and South America, particularly in the Amazon Basin.

The highest-risk groups include:

- People who inject drugs and share contaminated needles.

- Patients undergoing long-term dialysis treatment.

- Populations in areas with low HBV vaccination coverage, where HBV and HDV co-infections can spread more easily.

Because HDV requires HBV to survive, regions with high HBV prevalence are naturally at greater risk for HDV outbreaks.

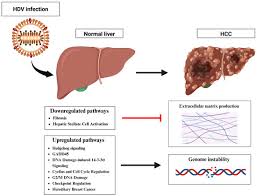

Why HDV Is Considered Cancer-Causing

HDV has earned its Group 1 carcinogen label due to multiple biological and clinical reasons that demonstrate its cancer-causing nature.

- Immune system damage – HDV infection triggers a more intense immune reaction compared to HBV alone. This heightened immune activity causes greater liver injury, which in turn raises the risk of cancer.

- Increased cancer risk – Studies show that people infected with both HBV and HDV are two to six times more likely to develop liver cancer than those infected with HBV alone.

- Faster disease progression – Around 75% of HDV patients develop cirrhosis (liver scarring) within 15 years, compared to about 50% in patients with HBV-only infections.

- Younger impact – HDV can cause severe liver fibrosis and failure even in young adults, accelerating disease onset and cutting short healthy life years.

- Mechanism of action – HDV uses the replication system of HBV, which increases viral activity and boosts its cancer-driving potential. This dual viral load speeds up the deterioration of liver cells.

The combination of these factors makes HDV one of the most aggressive liver viruses known.

Prevention and Treatment

At present, there is no direct vaccine for Hepatitis D. The only preventive measure is the Hepatitis B vaccine, which indirectly prevents HDV infection by stopping HBV in the first place.

For those already infected, treatment options are limited:

- Bulevirtide – an antiviral drug approved in Europe, often used with pegylated interferon. It is currently one of the few specific treatments available for HDV.

- Lifelong antiviral therapy for HBV – controlling HBV can indirectly slow HDV progression and reduce complications.

However, there are major challenges:

Testing for HDV is not routinely available in many countries, and the cost of treatment remains high. Many patients do not even know they are infected until liver damage is advanced.

Current Global Gaps

According to WHO’s 2022 data, significant gaps remain in the global fight against viral hepatitis:

- Only 13% of people with HBV and 36% of those with HCV have been diagnosed.

- Treatment rates are extremely low — 3% for HBV and 20% for HCV.

This lack of diagnosis and treatment is especially dangerous for HDV because of its aggressive nature. The virus often remains undetected until it has caused severe, irreversible liver damage.

The Road Ahead

The new classification of HDV as a proven cause of liver cancer is expected to be a turning point in global health policy. Governments and health agencies are now under greater pressure to:

- Expand HBV vaccination programs to prevent HDV indirectly.

- Improve HDV screening in all patients with HBV.

- Increase funding for research into HDV-specific treatments.

- Ensure affordable access to life-saving medicines like bulevirtide.

By strengthening prevention, testing, and treatment measures, public health systems can significantly reduce the burden of HDV-related liver cancer — one of the most preventable yet deadly forms of the disease.

Conclusion

Hepatitis D virus is no longer just a rare and severe form of hepatitis; it is now officially recognized as a direct cause of liver cancer. The WHO and IARC’s decision to classify HDV as a Group 1 carcinogen underscores the urgent need for global action.

While the absence of a direct HDV vaccine presents challenges, the HBV vaccine remains a powerful tool to block both viruses. Expanding vaccination, increasing testing, and improving access to treatment could dramatically cut the number of lives lost to HDV-related liver cancer.

The message from the scientific community is clear: tackling HDV is not just about controlling hepatitis, it is about saving lives from one of the deadliest cancers worldwide.